The Lost Children of the Alleghenies

The Lost Children Of The Alleghenies And How They Were Found Through A Dream

By Charles R. McCarthy

Huntingdon, Pa.

Journal Publishing Co., Johnstown, Pa.

To the parents of "The Lost Children," as a token of sympathy and esteem, this little volume is respectfully dedicated by the author.

PREFACE.

At the solicitation of a number of the older citizens of Blair and Bedford counties, (Pa.) I have consented to publish this brief and thrilling narrative. The subject is one that does not require the pen of a ready writer to make it interesting, but a mere relation of the fact as they occurred I think cannot fail to interest all.

Children are the most interesting and at the same time the most helpless of all God's creatures, so that until they have reached certain years they are entirely dependent upon others for food, clothing, and protection. They do not have the least knowledge of danger. But in order that they may be protected and provided for in their tender years, God has, by the touch of His finger, implanted that love that burns in the heart of nearly all parents for their children. It was this love that led David in the bitterness of his grief to exclaim, "O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom; would God I had died for thee." A railroad engineer, as his train approached his home that was near the road, saw his little three year old boy playing on the track. The situation was such that he could save his boy by losing his own life. He chose the latter alternative, and was instantly killed.

In 1874 when the news flashed over the wires that little Charley Ross had been kidnapped or stolen from his parents in Philadelphia, this entire continent was moved in sympathy for the little boy and his parents and friends. Such was the feeling that the name of Charley Ross became a household word in every family all over the land. His picture was sent to every part of the country. The press freely advertised him and gave the parents every possible assistance to find him, while thousands of letters of love and sympathy were written to them from every part of the United States and Europe. If half the children in Philadelphia had died in a single day it would not have created a greater sensation over the country than did the abduction of little Charlie Ross. No one can imagine what his parents have suffered. Yet through all these years of painful anxiety they have had some hope that their dear lost boy may one day find his way back to their home, not as the little boy now, but as a young man in all his strength of manhood.

They imagine that his abductors though fiends in human form, could not find it in their hearts to murder their innocent little victim, and that he still lives, perhaps in their own city. The parents have spent a fortune trying to find their boy, and would willingly spend their lives in the search. And now as he has been lost so long they no doubt have given up the search. Still they will live in hope that he may yet return. But not so in the case I am about to relate. If the narrative of "The Lost Children," was a romance or fictitious story I might couch it in entirely different language. But, as every part of it is literally true, the reader will pardon me for using as nearly as possible the language of those who were present at the time and witnessed the events as I shall relate them. The narrative is so sad and touching that even strong men to-day who helped to search for the lost children more than thirty years ago, are moved to tears while relating the story.

To the parents and relatives of "the lost children," and to the hundreds of generous hearted neighbors, who are still living, and who spent so many long days and wearisome nights in searching for them, this little narrative will come home with a touching interest that the strange reader far away from the wilds of the Alleghenies may fail to realize. Yet I believe the narrative possesses a merit separate and apart from all mere local and personal associations. It is hoped therefore that these pages may find many interested readers, not from any merit of the writer, but from the truthful and touching subject he represents.

Huntingdon, Pa., June 25th, 1888.

CHAPTER I.

The traveler going west over the Pennsylvania Railroad, as he approaches the Allegheny Mountains some four or five miles west of Altoona, is delighted with the wild scenery that meets his gaze. Here he is in the very midst of the Allegheny range, where the great barrier begins to break into the numerous spurs which lead away in long lines from the interior towards the east.

The iron steed boldly climbs the mountain on one if these numerous spurs, carrying the traveler up by an ascending grade of eighty-four and a half feet to the mile, but reduced to seventy-five feet by means of curves.

At Kittanning Point, the road is carried around a sharp curve which has ever since its construction been a wonder of engineering skill.

The art, or science, here must have been put to the sharpest test, and proved master of the situation. Two deep ravines had to be crossed, and to accomplish this feat, a point of the mountain had to be cut away and the two ravines by high embankments brought up to proper grade, then by a sharp horseshoe shaped curve, the sides of which are parallel with each other, the train is turned around in a moment's time, and on the opposite spur of the mountain has the appearance of running directly back to Altoona, the station it had left a few minutes before. But after completing the horseshoe bend, the road by use of another curve, turns to the right and passes on more directly westward, through the great gateway nature has opened for its accommodation, and through the long tunnel to Gallitzin. On leaving the horseshoe curve, the traveler is more delighted than ever with the wild mountain scenery, The gorge here is much deeper than at the horseshoe curve, and as the train carries him along the steep mountain side he looks down into the deep ravine some places, almost perpendicular, hundreds of feet below him; while another mountain rising abruptly on the other side, and running parallel with the one he is on towers far above his head. Before reaching Gallitzin, the train passes through a long tunnel which is three thousand six hundred and twelve feet in length, and securely arched throughout. The highest point attained by the Pennsylvania Railroad is at the western end of this great tunnel, where the elevation above tidewater is twenty-one hundred and sixty-one feet. This summit is known as Allegrippus Point. The entire distance over the mountain, is some thirty or thirty-five miles.

Hundreds of travelers every day between Altoona and Gallitzin are led, not only to admire with pleasure this wild mountain scenery, but alike the grand and daring engineering skill manifested in so successfully building an iron road over this formidable barrier. These scenes are so grand, and so romantic, that they never grow old.

Some fifteen or twenty miles south of this, in other wilds of the Alleghenies is the scene of our narrative. The scenery here is much like that described above, only upon a scale more extended. The different hills, cliffs, crags, and ravines have been named by old hunters, so that the people living near the foot of the mountain understand them. One of the highest points is known as Blue Knob, another Fork Ridge, others Blue Ridge, Cedar Swamps, Kings Cabins, Red Ridge, Hogback Ridge, Spruce Hollow, Gypsy Hollow, Bob's Creek, Ciana Run, and others.

The isolated farms and small improvements that can be seen in different parts of this vast mountain range look as if they had wandered away from civilization, and (like the children) been lost in the wilderness.

Spruce Hollow, is in Bedford county, Pa. From the mouth of this ravine to the top of the mountain, or to the settlements on the other side is at least fifteen miles, while the forest extends for many miles on either side. Over this vast mountain range are numerous rugged peaks and deep hollows, through which pass a number of creeks and mountain streams. During the spring months, when these streams are swollen by the melting of the snow, they rush down these deep ravines on their wild, mysterious errand as though each was trying to outrun its fellows in reaching the Juniata River below. And while this part of the mountain has numerous high peaks, hills and hollows, much of it is level and covered thickly with under growth timber and brush, making it difficult in many places to travel through it. And there is such a sameness about it that old hunters sometimes get lost and have trouble to find their way out.

CHAPTER II.

How the Children Were Lost.

Thirty-two years ago there lived in a little cabin, in Spruce Hollow, a family by the name of Cox. The family consisted of Samuel Cox, his wife, and two little sons. Mr. and Mrs. Cox commenced their early married life in Johnstown, Cambria county, Pa., and remained there until their two sons were born, when they moved to the State of Indiana, in 1851. But unfortunately for them, they settled in a part of the state where malaria fever prevailed, and soon their little family was prostrated with the disease, and for weeks and months, they lingered between life and death, until for the sake of life and health, they were compelled to move back to their native hills in Pennsylvania. Soon after returning they settled in this lonely spot in the wilds of the mountain as their future home.

It is evident that they had no desire to be rich or they would never have selected Spruce Hollow as a place to gain wealth.

But being naturally of a contented turn of mind it did not require much of this world's goods to make them happy. And now that their children were fast gaining health from breathing the pure mountain air they felt entirely satisfied with their lonely retreat and with the thought that their children might be a blessing to them now, and a comfort to them if they should live to declining years. With such musings in their minds they felt perfectly happy.

But alas! with them, as with all others, how uncertain are all earthly enjoyments. Grief and woe unutterable was at their very door, and they knew it not. The dark cloud without a silver lining was fast gathering over their heads and they had no knowledge of what a single hour would bring forth to them.

It was on the 24th day of April, 1856, that Samuel Cox while at breakfast heard his dog barking in the woods about one-eighth of a mile from his cabin, and, as his dog usually had a squirrel treed when he barked this way, Mr. Cox remarked to his wife that if his dog should continue to bark until he was through his breakfast he would go out and shoot the squirrel. Hastily finishing his meal he shouldered his gun and started out in the woods in the direction of his dog, leaving his two little boys at the table with their mother. Failing to find the squirrel he shortly returned to his cabin by a different route from that he had taken in going out. Not seeing the children, he inquired of their mother where they were.

She had not noticed them after they had gone out from breakfast. As there was but little cleared land about their cabin it did not require long to determine that they must have undertaken to follow their father to the forest. The parents in the wildest alarm ran to the mountain, and taking in as much of it as they thought it possible for their children to have reached in so short a time, they made the most careful search without finding them. Then they returned to their home thinking the children might have come back to their cabin during their absence but in this they were sadly disappointed. The parents, now almost distracted, made the fact known to their nearest neighbors that their children were lost in the wilds of the mountains. The news spread like wild-fire, and while many hastened to the mountain to help search for the lost ones, others on foot and on horse, traveled from house to house, and from one village to another, carrying the news. Every one that heard it seemed at once to comprehend the situation, that whatever was done to find them must be done quickly or they would not likely be found at all. With this kindred feeling in the minds of nearly all who heard the tidings it is not at all strange that plowman unhitched their teams midway in the fields, merchants closed their stores, mechanics threw down their tools with their work unfinished, and all, with one common purpose, hastened to the mountain, and notwithstanding the day was far spent before many of them heard the news, yet so quick were the people in their efforts to rescue the little perishing ones, that not less than two hundred voices rang along the crags and cliffs of the Allegheny ere the sun had set on that day. So thorough was the search that every plane, hill top and ravine within a reasonable distance of their home had been carefully gone over before dark without finding even a foot print of the lost children. And what alarmed the parents still more was, that as night approached it was fast growing cold, dark heavy clouds were looming up in the north-west, and as it was in the dark of the moon everything indicated a dark and stormy night. The father, worn out with exertion and grief, plead with his neighbors to continue the search through the night.

"For how," he thought, "can they possibly live through this dismal night exposed to the wild beasts of the mountain, without a shelter to protect them from the snow that is fast falling, without a place to lay their weary heads, or a morsel of food to strengthen their feeble and exhausted bodies." Willing to do anything to comfort the bereaved parents, quite a number remained out all night and kept up fires on different points of the mountain, thinking the children might be attracted to the lights, while others returned to the home of the parents, if possible, to speak words of comfort to them.

Grief sometimes reaches a point when friends, though stored with words of comfort, do not seem to have the power to express them. So it was in this case. The grief of the parents was so great that those who had gone there for the express purpose of consoling and comforting them could only look on in silence and weep with them.

It is not at all strange that the parents should feel heart-broken at the loss of their little boys. They were very innocent, interesting children. George, the elder one, seven years old, had dark hair and blue eyes; while Joseph, the younger one, aged but five years, had light hair and gray eyes; and, owing perhaps to their sickness in the west, they were small for their ages, but in cuteness and knowledge, they were far in advance of their years. George was remarkably intelligent for one of his age, and always had such a care for his younger brother, that when going to and from their play, he nearly always led him by the hand and they were so affectionate with one another that they never had a quarrel at their play.

Young loves, young hopes dancing on morning's cheek,

Gems leaping in the coronet of Love!

So beautiful, so full of life they seemed

As made entire of beams of angels' eyes,

Gay, guileless, sporting, lovely little things!

Playing around the den of sorrow, clad.

In smiles, believing in their fairy hopes,

And thinking man and woman true! All joy,

Happy all day, and happy all the night.

CHAPTER III.

The False Accuser.

The first night the children were out on the mountain was the longest night the parents had ever experienced; and, notwithstanding so many of the neighbors were spending the night with them, they never felt so lonesome before. Without their boys all was dreary and sad, and how slowly and sluggishly the hours passed away. Morning came at last, but without a single word of comfort for the sorrowing parents.

The day came in cold and damp, with thick heavy clouds, and the north winds were piercing even those well clad. The severe weather seemed to touch the heart of every one in sympathy for the little lost wanderers, who, if living, were far away on the cold mountain, with but little clothing to screen their tender limbs from the biting frost, no fire to warm them in their painful wanderings, nor a taste of food to nourish them in their fatiguing journey among the brambles, swamps, and rocks of the mountain. With such a general tenderness and compassion in the minds of the people it is not at all strange that the day had scarcely opened until scores, and hundreds of people were seen coming from every part of the country to aid in the search. They came in groups and bands, and with one purpose in view they all hastened to the mountain. And while a few traveled over the same ground that had been explored the previous day, thinking that the children might have wandered back to these parts, others took a different direction so that the adjacent hills and vales were everywhere explored; every thicket, marsh, and cliff was searched till all the dells and craigs for miles resounded with the call of the hunters for the lost. But no response was returned. The day was fast passing away without a single sign or trace of the lost children. And as the dark night came upon the world the parents felt more disconsolate than ever. The past day's search had failed to discover even a foot-print of their lost and starving children.

Another long, lonely night to the heartbroken parents passed slowly away, and the bleak and dreary morning set in. But so persistent were the good people in their search that before ten o'clock not less than one thousand people had gone away in search of the children. Far and near, all over the face of the mountain, for miles around were scattered hundreds of searchers. From the deep recesses of the rocky glens, to the far up ragged peaks of the Alleghenies were seen the busy hunters, searching every retreat, examining every nook, and exploring every defile, with the anxious expectation of finding the children. But all exertions seemed in vain. Another day closed with cold and stormy weather, and with less hope of finding the children alive than before. The night passed. Another day came with the weather still inclement. And, what was remarkable in the case, as the prospects of finding the children grew less hopeful every day they were lost, the efforts and exertions of the people to find them increased each day until perhaps there were two thousand people on the mountain. And still they came in multitudes from every part of the country and the number was still increasing. Now, as every effort to find them up to this time had failed to bring one word of comfort to the sorrowing parents, it did seem to the sympathizing thousands who had kept up the unsuccessful search so long, that the parents cup of misery must be full to the brim. But they were mistaken. One drop more was wanting; and there was a Judas in the company of kind sympathizers ready to add this. As in the case of Charley Ross this fiend in human form charged the parents with murdering their children for the purpose of getting money through compassion of the people. This wretch, in company with a few kindred spirits, had the audacity to take up some of the floor in the parents' cabin, to see whether or not they had buried their children under the floor, and dug up some places in their garden where they had buried their potatoes for the same purpose. It was only a man who had a heart in him to murder his own children that could have thought of such a cruel act. And when the news was carried abroad that such a charge had been made the people were so indignant at such an unreasonable accusation, that they would have punished this wicked party according to their evil deeds, had they not escaped from the company and remained away. Soon after this, as if to disprove these slanderous charges against the parents, a murmur came through the neighborhood and ran along the mountain that traces of the little wanderers had been discovered. With such a rumor every heart beat high with hope. Then came the news that their little tracks were plainly seen far out in the sands of the unbroken forest at least ten miles from their home. The hunters were so arranged on the mountain that they were within speaking distance of each other. So it did not require long to carry the news from the most distant points. Hundreds of people gathered to the spot where the tracks had been found, and starting from there they moved out in every direction, believing that the lost children would soon be found; and the search was now pursued more vigorously than ever before. But all were disappointed when the day closed without another mark or foot-print of the little wanderers. The parents had been much encouraged with the news that tracks of their children had been found far out on the mountain. This led them to believe that they were still alive.

But as night had again closed in upon the thousands of diligent searchers without finding more than a few foot-prints, they were more disconsolate than ever. Another useless day's search was completed, and another dark night with all its gloom, had come upon the world. The winds that had blown on the mountain almost constantly from the time the children were lost, now ceased to blow, and a mournful stillness rested upon the surrounding forest. No voice nor sound, disturbed the silence of the wilderness, save now and then the howl of the distant wolf, or the scream of the wild cat and panther, as they broke through the darkness, and brought to many a heart a fearful sadness for the lost ones, who, if still living, were exposed to attacks from these wild beasts. Many now were the views, the conjectures and speculations concerning them. Some said it could not be otherwise than that they had been devoured by the wild beasts that abounded in the mountain, as no trace or sign of them could be found. Others would have it, that they had been taken away by a gang of Gypsies, that had been strolling through the country. Some supposed that they had been stolen and placed within the walls of a secret religious institution to be educated in their peculiar faith. Others believed they had fallen into some of the mountain streams and were drowned. But the great majority of the people believed that they were still alive wandering about in the wilds of the mountain, and that people should double their exertions to find them.

CHAPTER IV.

The Superstitious Hunters and the Witch.

Up to this time the search for the children had been kept up in a systematic way. Some one well acquainted with the mountain, was appointed each day as a leader or captain. He would arrange or align the people at such a distance from each other that they would be able to scan every foot of ground within their line of march. Every fallen tree was to be examined and around the base of every rock and the mountain streams also were to be searched, as many believed they had fallen into some of them and were drowned. And while the great mass of the people took a different course on the mountain each day, some would travel over the ground already gone over, supposing that the children in their wanderings might have gotten back to that part of the forest so carefully searched before.

Some five or six nights after the children were lost a woman by the name of Bentamer, living near the foot of the mountain, distinctly heard a child crying far out on the mountain at a late hour in the night. She managed to carry this news to some of her neighbors, and a vigorous search was made, but to no purpose. It is supposed to-day that this woman really heard the lost children cry; but by the time the people got to the place the children perhaps had cried themselves to sleep -- so that with the most careful searching they might easily have passed them by in the dark. They were never heard to cry again.

The most remarkable thing connected with the story I am narrating was, that the people never seemed to weary or tire hunting for them. Although every foot of ground where it would seem possible for them to have wandered, had been gone over time and again yet hundreds of people were added to the searchers daily, all united in one common purpose, never to give up the search until they had found them either alive or dead; and after so many days and nights of fruitless search for them, the most hopeful, had but little idea of finding them alive.

Samuel Cox and his wife were opposed to all forms of sorcery, magic, or necromancy. They had no faith in witches or wizards. But some of their neighbors, who had spent much time, both day and night hunting for the children, were firm believers in all kinds of charms and sorceries. There was a colored man living somewhere in Morrison's Cove, who had revealed some very mysterious things by the use of a peach-tree limb. This man was sent for to practice his art or magic. When he came to the home of the lost children he procured a forked peach-tree limb, with the branches of equal size. Then taking a branch in each hand he held it up at arm's length in front of him, with the point where the two branches united pointing upwards. Then he commenced moving slowly around in a circle, and when he came to the direction the children had gone or the place they would now be found the top of the branch would turn in his hand and point in that direction, and would remain in that position just as long as he traveled in the direction of the children. But if he lost his bearing the top of the stick would turn back and point toward him. This man could tell of many mysterious things he had discovered with the peach-tree limb. He could tell to an inch where a stream of water could be found hundreds of feet beneath the surface, and he could tell exactly where two streams met, and many other things. He was very confident, as well as those who had brought him on the grounds, that he could soon lead them to the lost children. It did not require long, however, to discover that he and his peach-tree limb were a fraud and had it not been for those who were with him, he would have been lost in the mountain himself.

But the believers in sorcery and witch-craft were not to be discouraged with one failure. There was an old witch living in Somerset county who was noted for her conjuring power, not surpassed perhaps by the witch of Endor. After holding a consultation, it was determined by a few of the superstitious to send for her. The old lady, on arriving at the mountain, went through a number of mysterious conjuring tricks, after which she said she knew where the children were; she could see them plainly -- that they were far out in the interior of the mountain, living and subsisting well on chestnuts that had lain on the ground over winter. She said that they lodged at night on a nice bed of leaves under a heavy bunch of laurel that protected them from the rain and snow. But she said, "I can't find de children unless you gif me some money." Her conditions were complied with. "Now," said she, "Jes you foller me and I'll soon find de children -- if you had jes sent for me fust, you might have had em long ago. Again ten o'clock tomorrow we'll have em safe a nuff. De childers all right."

The poor old deluded creature now with staff in hand started out with quite a number of searchers, she leading the way. But they were soon interrupted by night coming on. The night was dark, cold and rainy. But when morning came as usual, it brought hundreds and thousands of people to the mountain, and quite a number who did not have any faith in witches accompanied the old enchantress, curious to know how her conjuring would end.

The reader can imagine the sorcerer, as she leads the way, and see her as she ascends the rocky heights of the Allegheny. After passing rugged hills and crossing timber, obstructed vales, and swollen streams that had been more than thrice explored before, she enters the barren wastes of the interior of the mountain. Ten o'clock came, and eleven and twelve passed by, and yet, the place nor children were not found. But on, and on, the charmer went, still declaring to those about her that they should soon see the lost children. And thus they went on wandering through the wild and dismal forest until night began to shroud the valleys below in gloom; she at last sunk down, faint, and exhausted, and declared that she could go no further without sleep and rest, but that in the morning she would be able in a little while to reach the children and save their lives. Fires being made, the company passed another inclement night on the mountain, and in the morning, after taking a hunter's meal, they again set out to find the children, the old woman, as usual, taking the lead, and affirming with more confidence than ever, that she would soon bring them to the object of their search. But hour after hour passed away without discovering even a foot-print of the lost ones. And those who had watched her closely during the search could plainly see that she was completely lost herself, that she had no knowledge where the children were, and that she was just leading them round and round in the tangled woods, until wearied and wornout, she seated herself on a log and declared that she could go no further, that she was too ill to make further effort, and that she must return. And had it not been for the aid of those who had accompanied her, she herself would never have found her way out of the wilds of the mountain. It is hardly necessary for me to state that those who were favorable to having this old imposter on the mountain to practice her magic tricks felt ashamed that they had been so easily duped. Now, while a small portion of the people were following this man and woman practicing their magic tricks, hundreds and thousands were keeping up a constant search from hill to hill, and from one ravine to another, until almost every foot of the mountain had been gone over time and again, where it would seem possible for the children to have wandered. Yet at the dawning of each day came the excited thousands. Neither time, money nor exertion was spared. The whole adjacent population seemed determined to ascertain what had become of the lost brothers. Far and wide over the mountain region the surrounding country poured out its inhabitants. Other fields and other forests were traversed and more distant wilds explored each day. And as the thousands of hungry and exhausted searchers returned at the close of each day they found that provisions plenty and to spare had been provided for them. The ladies everywhere throughout the excited vicinity exerted themselves to provide the hunters with food as they came in hungry from the search.

CHAPTER V.

The Dream and Where the Children Were Found.

Ten days and nights of constant search by hundreds, and thousands of people had now gone by. Ten long days and sleepless nights had passed away with the disconsolate parents of the the lost children, and with less hope of finding them now than ever before. No one can imagine how much they suffered from anxiety and suspense. It would have been a relief to them to have known that their children were dead and at rest; but even this seemed to be denied them.

On the tenth night after the children were lost, a man by the name of Jacob Dibert, living some twelve or thirteen miles from the place where the children were lost, and who, up to this time had taken no part in the hunt for the children, and who had little or no knowledge of that part of the mountain, dreamed that he was out alone searching for them. In his wanderings he dreamed that he came to a dead deer. Further on he found a little shoe. Next he came to a large stream, the name of which he did not know, (it proved afterward to be Bob's Creek, which I have already mentioned.) He crossed this stream at one of its narrowest places on a beech log. Then, in his dream, he traveled over what is known as Blue Ridge and entered a ravine or narrow valley through which flowed a small brook that came out of one of the mountain gorges. Following this brook a short distance he came to a birch-tree, the roots of which formed a semi-circle, and in this little circle, on the very margin of the stream lay the lost children, dead. Just at this point of his dream he awoke, and the whole scene was so clearly impressed upon his mind that he could scarcely be convinced that it was only a dream.

Mr. Dibert was an intelligent man and was in no way superstitious. He had no faith in omans or dreams, and really he had no reason to believe in them, as non of his dreams up to this time had ever come true. The last one, however, was not to be banished from his mine. He frequently talked to his wife about it during the day, and asked her, as she had been brought up near this part of the Allegheny, whether there was such a place on that part of the mountain as had been indicated in his dream. She told him there was just such a place on that part of the mountain.

On the second night he had precisely the same dream over again. This impressed him more fully than ever that his dream was true; yet he hesitated to tell his neighbors about it, fearing they might call him crazy. He would willingly have gone out himself to test the truthfullness of his dream, but he did not have any knowledge of the forest, and feared he might get lost himself. The third night came, and he dreamed the same dream over again. He came up the same hollow; passed again the dead deer; saw again the little worn shoe that the weary little wanderer had put off for the last time; crossed Bob's Creek on the beech log he had seen in his first dream, and where probably the little children had crossed it; passed again over the Blue Ridge, and came up the little ravine to where he saw the birch-tree, and the stream by whose babbling waters the tired, hungry, suffering little lambs had laid them down to sleep, to wake up in the arms of Him who said, "Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God."

Mr. Dibert felt so sure now that his dream was true that he started on the following day to his wife's brother, Harrison Wysong, who lived some twelve miles away, and near where he had dreamed the children were. When he told his brother-in-law about his dream, and that he had come to get him to go with him to find the place he had seen in his dream, his brother-in-law thought him crazy. He said that the place he described was five or six miles away from the home of the children, that they could not have traveled so far, and if they had they could never have gotten over Bob's Creek, which is a large stream. None of the searchers had looked for the children on the east side of the stream. None supposed for an instant that they could have crossed it without being drowned. Harrison Wysong used his best arguments with his brother-in-law, to dissuade him from going on such a wild hunt. "Very well," said Mr. Dibert, "if you will not accompany me I will have to go alone. I am going at any rate."

Failing to dissuade him, the brother-in-law went along, for knowing that Mr. Dibert was not acquainted with the country, he feared that he would be lost if he went alone. Going in the direction indicated by Mr. Dibert, they presidently passed a dead deer; looking, Mr. Dibert said, "Just as I saw it in my dream." Further on they found the little shoe which had been worn by the younger of the two children. Then they came to Bob's Creek. "Here," said Mr. Dibert, "is the beech long where I crossed the creek." As they passed along, the route seemed as familiar to Mr. Dibert as if he had been over it many times before, though he had never been there except in his dream. Passing over Blue Ridge, and to the ravine, down which the mountain stream flowed, and down this stream, the woods became more open so that the travelers could see some distance ahead. "This," said Mr. Dibert, "is just like I saw it in my dream; and if my dream is true, we will soon be at the place. Do you see that tree with the broken top on the edge of the stream? If my dream is true that is a birch-tree and the boys are lying at the root of it." And sure enough the tree was a birch and there lying cold in death were the worn emaciated bodies of the poor, lost children, just as he had seen them in his dream.

CHAPTER VI.

Mr. Dibert a Soldier.

Mr. Dibert was a soldier in the late war, and died while in the service. His widow, now Mrs. Gardner, of Pavia, Bedford county, Pa., writes me the following letter which though not intended for publication, I think will be interesting to the reader.

Pavia, Bedford County, Pa.,

April 7th, 1888.

Mr. C. R. McCarthy, Huntingdon, Pa.

Dear Sir: -- I herewith send you a statement of the facts connected with finding of Cox's lost children, so far as my husband had anything to do with it. My husband, Jacob Dibert, and myself lived on a farm in Blair County, Pa., about three miles from the village of Claysburg in said County. From where we lived to where the children were found, was a distance of about 12 miles. The children were lost on Thursday, 24th day of April, 1856. On the following Sunday which was the 27th, at church was the first that we heard that the children were lost. During that week we heard a good deal of talk about the children not being found. On the following Saturday night which was the third of May, my husband and myself were talking about the poor lost children, as we had several about the same age, we felt much distressed about them. My husband said he wished that he could dream where the lost children were. Next morning he told me that he had dreamed that he found the lost children, and he gave me a description of the place, which he said was in a little valley between two large hills, and that a small stream of water ran through the valley, and that the children were dead, and lying very close to the banks of the stream at the roots of a birch-tree, and that this valley was on the east side of a large stream of water. He was not acquainted with the woods in that locality and he asked me if I knew of such a place and valley. I answered that I did, for I was raised within about two miles of that place on my father's farm, and that I frequently brought our cows from that valley. The next night, which was Sunday night, he dreamed the same dream again. On Monday night he dreamed it over again. The place where he found the children to where their parents lived, on a straight line, is fully five miles, and on the west side of the large stream. He was very anxious and could not rest, and tried to get some of the neighbors to go with him, but none would go because everybody said it was impossible for the children to cross over the large stream because the waters was high. He asked me if I thought they might, or could cross over the high stream. I told him I thought they could if they would go up the stream a long distance, because trees fell across it, and there were drifts that they could cross over on. I told my husband to go up to my father's place. He started on Wednesday, the 7th of May, about 3 o'clock P. M. My father was not at home, so he went to my brother Harrison's, which was but a short distance away. Either of them were well acquainted with the locality of the place where he dreamed he found them. He told brother Harrison that he had dreamed three nights in succession that he found the lost children, and that he had come to get him to go along to the place. Harrison told him that he was getting crazy, that he had a notion to boot him and send him home. My husband replied, "I am not crazy, but I want you to go with me to the place.' Next morning they started early, and after traveling awhile my husband said, "there is the place, and there is the birch-tree with the top broken indicated in my dream." And when they got close enough to see, sure enough there the children lay just as he had dreamed, and close by the stream. The name of the stream along which the children were found in English would be Gypsy, and in German, Ceina. The hill on the right as you go up stream is called Red Ridge, and the one on the left Hog Back.

Jacob Dibert, my husband, enlisted in the late war on the 8th day of September, 1861, (in Company K, 55th Pa. Vols.) Re-enlisted last day of December, 1863, was appointed Corporal December 20th, 1861. Died at Point of Rocks, Va., October 26th, 1864, and was buried at that place, where his remains still lie. He died of chronic diarrhoea. He was in a dozen or more hard fought battles while he was in the service.

Harrison Wysong, who was along with Jacob Dibert when the children were found, is also dead. He died in Clearfield County, about twelve years ago."

MRS. SARAH GARDNER,

Pavia P. O., Bedford Co., Pa.

Mrs. Gardner is an intelligent woman, and has a remarkably good memory. The above letter is given in her own words, and although not intended for publication, I think the reader will agree with me, that her statements are very clear and satisfactory. She had often told this story of the lost children to her own, and other young people, and she is anxious that they should see it in print.

Now the fifteenth and last day's search had come. The morning was clear and beautiful, and the sun had scarcely touched the hill tops ere the assembling hundreds could be seen on their way to the forest to renew their search. Already had the farmers' plows been standing fourteen days with their fields half plowed, at this throng season of the year, while mechanics had left their unfinished work, and had gone day after day to take part in the search. It is said that the willing and benevolent people had already donated over five thousand dollars in provisions, money, and other necessaries to carry on the search for the lost ones. The mountain was now echoing with voices and marching of two thousand people all untiring in their search.

Mr. Dibert and his brother-in-law, Mr. Wysong, had already gone out in the direction of the Blue Ridge, the point designated in his dream. And as the people had no faith in his vision, no one had accompanied him but his brother-in-law. This was a part of the mountain that during the fourteen days of careful searching by thousands of people, no one had yet explored, for the reason that it was deemed impossible for the children to cross over Bob's Creek, a large stream, as they would have to in getting to this part of the mountain. This was in part the reason why they had no belief in Mr. Dibert's dream.

About 11 o'clock in the day the signal was given that the children were found. At first the sound was borne on the breeze so faint and indistinctly that you could scarcely believe your own ears. "The children are found." Then louder and louder, the voices rose to a shout and echoed along the hills. "The children are found! The children are found." Then swelling louder, and louder, until like the echoing of the tempest, the mountain resounded with the voices of hundreds answering back to hundreds that the lost children were found. Then began the hurried march of the excited multitude to the place where the bodies lay. Soon the long lines of the approaching hundreds came in from every point of the compass. As each one approached he took a position as near as he could to the dead children, and solemnly awaited the coming of the father. When he came, he was so overcome with grief, that he had to be assisted to the place, and when there he bent over the little forms and wept bitterly. Every one present was touched in sympathy for him.

CHAPTER VII.

The Children Starved to Death.

In that part of the mountain where the children were found there was nothing for them to subsist upon, not even mountain tea. Their bodies were wasted to mere skeletons, their limbs were scarred and lacerated from traveling through the thorns and thickets of the mountain. Their clothing was worn out, and hung in shreds about their emaciated forms. Their little shoes were almost worn through, although they had been newly soled. It was evident that they had wandered over the rocks and wilds of the mountain until completely worn out from fatigue, and crying for bread. They had lain down and died of exhaustion and starvation. Physicians supposed that they had been dead some three or four days. That Joseph, the younger one, had died first, and George, the elder one, had taken a little smooth stone out of the brook and with his hat upon it had placed it under his brother's head for a pillow. Then, taking his seat beside him, we can imagine him bending over his cold and lifeless body faintly calling him to awake, and wondering why he slept so long, until worn out with hunger and cold himself, he fell over by the side of his brother, where they both lay side by side, in the cold sleep of death. As soon as it could be procured, a sled was brought to the place, the remains of the children were placed upon it, and they were taken to their father's home some six or seven miles from the place. And there they were kept until the following Sabbath, when the funeral took place. It is said to have been the largest funeral ever known in this section of the country, before or since. It is thought there were about five thousand people present. A number came from Pittsburg, Johnstown, Bedford and other places. Many came through curiosity to see the children.

The children were both put in one coffin. And a very affecting sermon was preached by Rev. Mr. Long from the 7th chapter and 9th verse, Rev., after which they were buried in Mount Union cemetery, Bedford. county, Pa. Some one, or more, had offered $50.00 to the party finding the children. Messrs Dibert and Wysong generously appropriated this money to purchasing tombstones to mark their graves.

On the third or fourth day of April, 1888, the writer, in company with Mr. Jacob Conrad, of Newry, (Pa.,) as a guide, visited the place where the children were found. Mr. Conrad is an intelligent, genial old gentleman, with a very good memory. He was one who helped to take the children to their home, and prepared them for burial.

The little smooth stone that George the elder one had taken out of the brook, and placed under his brother's head, is laying in the very spot where the little head was taken off it thirty-two years ago. Some of the bark has been cut off the birch-tree and carried off by the people as souvenirs. Some names have been carved upon it, and a number of trees have been marked around it as pointers. I am informed by those who were present at the time the children were found, that the birch-tree has changed but little in size during the thirty-two years. Since that time much of these wild lands have been cleared. But I venture to say if any stranger to the country were placed at the roots of this birch-tree today, where the little boys met their sad fate, he would have as little knowledge as they, as to what course he should take to get out of the mountain. Nothing to be seen from this point but a vast wilderness.

Let us now for a little imagine what these poor little boys must have suffered in body and mind, until death came to their relief; and the conversation they may have had to each other about their lost condition.

When they entered the woods first perhaps they could see their father in the distance, but soon he disappeared from their view in the wild thickets of the mountain. For a time they ran after him, but failing to see him, or hear his answer to their call, they decided to return to their home. But when they turned around, home, like their father, had disappeared. They ran around now in almost every direction crying, and calling their father. They hear the echo of their own voices up the glen and imagine it is some one answering their call, and they try to follow the sound, but every moment is taking them farther from home and mother, the very one they are so anxious to find. They had never known perhaps what it was to suffer hunger, a kind mother always had their meals ready for them at the proper time, and often a piece between meals, when they really did not need it. Now they were starving for bread, and pinched with cold, no dinner, and no supper. The snow is fast falling upon them and wetting their little garments, and they have no bed, shelter, or covering. The gloomy night is fast closing in upon them, and like all other children, they fear the darkness. They had often, no doubt, from their home, heard the wolf howl, and the panther, and wild-cat scream on the mountain, and had trembled at the very sound of them, with father and mother to protect them. Now they were in the midst of these wild beasts all alone. And no doubt they hear the distant wolf howl and imagine he is coming toward them. They call for help, until they cry themselves to sleep. But the pangs of hunger and pinching cold soon wake them up again to cry for help. Hungry and cold they start out early in the morning and make every effort to reach their home and save their lives. George, in his manly way, leading his little brother over the mountain streams, through the swamps, down into the deep ravines and over the high peaks; for all this they must have done in order to get to the place where they were found. In vain they cry for help; for father and mother. The pangs of hunger seem past endurance, while they are sorely pinched with cold. The piercing winds seem to mock at their little light garments, and thus they spend day after day, and night after night, wandering around in the mountain until completely worn out with fatigue, hunger and cold, they lie down and die. We may reasonably suppose that George the elder one, as was his custom, would speak words of comfort to his younger brother, as he led him along, trying to find their home. He would plead with him not to cry, that they would soon get home to mother. It can be seen that the last act of his life toward his little brother was full of love and tenderness. When he took the smooth stone out of the brook, placed his little hat upon it, and put it under his head for a pillow, while he would take his long, and last sleep. What more could he have done?

After leaving the scene at the birch-tree in Ciana Hollow, on the same day we visited the home of Mr. Samuel Cox, in Spruce Hollow. He and his wife are both living, and we found them quite a venerable social old couple. They make the stranger feel welcome, and at home, as soon as he crosses their threshold. They converse freely about their lost boys. But you can see that a shade of melancholy passes over them when their names are mentioned. The mother when asked whether she had ever gone to the place where her children were found, said, that she had not, that she had started with some of her friends two years ago to visit the place, but when she got almost there, her courage failed her. She felt that she could not endure the sight. So the reader will see how tender her feelings are on this subject. And notwithstanding more than thirty-two years have passed by, since her little boys wandered from her home never to return, she thinks of them every day, and in her imagination she can see them as they sat at her table taking their last meal with her, as clearly as though it had occurred but yesterday. Their home now is in sight of the place where they lived when their children were lost, some two or three hundred yards distant. Samuel Cox is seventy-six years old and his wife is sixty-one. They are both well preserved people, and are young looking for their ages. Mr. Cox was soldier in the late war. And the reader will see that his age would have exempted him from military service. But being a true patriot, he volunteered to serve his country. Mr. Cox and his wife have for many years been consistent church members. Therefore they do not feel today, that their little boys are lost but gone before, and that they shall soon meet them on the other shore never to be separated again.

There is a reaper who's name is Death,

And with his sickle keen,

He reaps the bearded grain at a breath,

And the flowers that grow between.Shall I have naught that is fair? saith he;

Have naught but the bearded grain?

Though the breath of these flowers is sweet to me,

I will give them all back again.He gazed at the flowers with tearful eyes.

He kissed their drooping leaves;

It was for the Lord of Paradise

He bound them in his sheaves.My lord has need of these flowerets gay,

The reaper said, and smiled;

Dear tokens of the earth are they,

Where he was once a child.They shall all bloom in fields of light,

Transplanted by my care,

And saints, upon their garments white,

These sacred blossoms wear.And the mother gave, in tears and pain,

The flowers she most did love;

She knew she should find them all again

In the fields of light above.O, not in cruelty, not in wrath,

The Reaper came that day;

'Twas an angel visited the green earth,

And took the flowers away.--Longfellow.

I will here give the epitaph or inscription on the headstone in Mount Union Cemetery marking the last resting place of little George and Joseph Cox.

George S.,

Born March 30th, 1849, and Joseph C., Born Oct. 29th, 1850.Sons of Samuel and Susannah Cox. Wandered from home April 24, 1856, and were found dead in the woods, May 8th of the same year, by Jacob Dibert and Harrison Wysong.

Bedford, Pa.

CHAPTER VIII.

Another Dream.

In connection with this narrative I will tell of another dream of more recent date, that also proved true. Sometime in the month of September, 1887, Miss Cidney Griffith, of Pavia, Bedford County, traveled in a buggy with her brother about twelve miles over the Allegheny mountain to Portage, a station on the Pennsylvania Railroad to see her father who was sick. Her brother left her at her father's on Saturday, and drove back to Pavia, promising to return for her on Monday. On Monday morning Miss Griffith, thinking she would save her brother the trouble of driving so far, started out on foot early in the morning to meet him, and lost her way on the mountain, by mistaking an old log road for the public road. Soon she was completely lost in what is known in the Alleghenies as the Cedar Swamps. These swamps are several miles in length and width, so that no one could have been lost in a more dangerous place. Miss Griffith became very alarmed at her situation. She could hear the locomotives whistle at Portage, the place she had left in the morning, but was so much excited and bewildered, that she had no knowledge what direction she should take to get there. In the meantime her brother had gone on to Portage with the buggy, and there learned that his sister had started out on the Allegheny road early in the morning to meet him. He knew that she must be lost on the mountain, and made it known to the people in the neighborhood and they turned out in great numbers to search for her; but with the most diligent efforts possible, night closed in upon them without finding her. No one can imagine the feelings of Miss Griffith on that memorable evening when dark night came upon her. She was suffering from hunger, as she did not have anything to eat from the early morning. She was weary from wanbering around through the swamp trying to find her way out, and she did not have a place to lay her head, or covering to protect her from the chilling night air. She thought of the story her father and mother had often told her when she was a little girl, of the Cox children who were lost on the same mountain, and were not found until they had starved to death. And she had every reason to believe now, that she should share the same fate. She dreaded the wild beasts of the mountain and had good reasons for her fears, as she soon heard the wild-cat or panther, she know not which, screaming in the distance, and seemed to be coming toward her. They came very near her during the night, but did her no harm except to frighten her. The night seemed very long to her, but toward the break of day she slept a little; and when the morning came, she determined just to remain where she was, that the chances to find her would be much better than if she would get to wandering about. She frequently hollowed during the day at the top of her voice but heard no response save the echo of her own voice. As the clouds had the appearance of rain with the second day, she fixed up a covering or shelter with bark over some logs to protect herself from the rain. But as it rained heavily all night, her roof leaked and kept her awake, so she could not sleep at all. And again the wild-cats screamed around her, until she trembled with fear, not knowing the moment they might spring upon her.

Now for two days and two nights Miss Griffith was in this pitiable situation, without one morsel of food, and every effort to find her had failed. On the second night after she was lost, Mr. Isaac W. Dibert, a young man living near Pavia, Bedford County, Pa., dreamed that Miss Griffith was lost in the Cedar Swamps, and in his dream he could see her so clearly that he was able to go to the very spot the next morning. This Mr. Isaac Dibert is a son of Jacob Dibert who dreamed of the Cox children. In April last the writer had the pleasure of an interview with Miss Cidney Griffith, at her store in a little town called Texas in Bedford County, near Spruce Hollow. As I had heard of her misfortune in being lost in the Alleghenies, I felt curious to hear her tell the story herself. She is quite an intelligent lady, and can tell you much of her experience during the two days and nights she was lost; but says that her mind was so much agitated that she cannot remember all that occurred. Few women, perhaps, in her perilous situation, would have acted as wisely, and with as much composure. Her remaining at one place was the best thing she could do. If she had managed to make her way out of the swamp would only have been to get into other, and more difficult wilds of the mountain. Miss Griffith, has learned a lesson that she will never forget. She will never undertake again to meet anyone half way on the Allegheny mountain.

Click to see J.C.Dibert's General Store.

Download Lost Children of the Alleghenies eBook.

Download the Lost Children of the Alleghenies eBook in ePub, PDF, and mobi (Kindle) format and eBook reader by clicking the book cover on the right.

I have all four readers and they work well for me. All are simple to use, updated often, and very mature.

I used Scrivener to produce these eBooks. If you are a writer, you need this software. Lightweight, fast, powerful, easy to use, and affordable. Designed for writers.

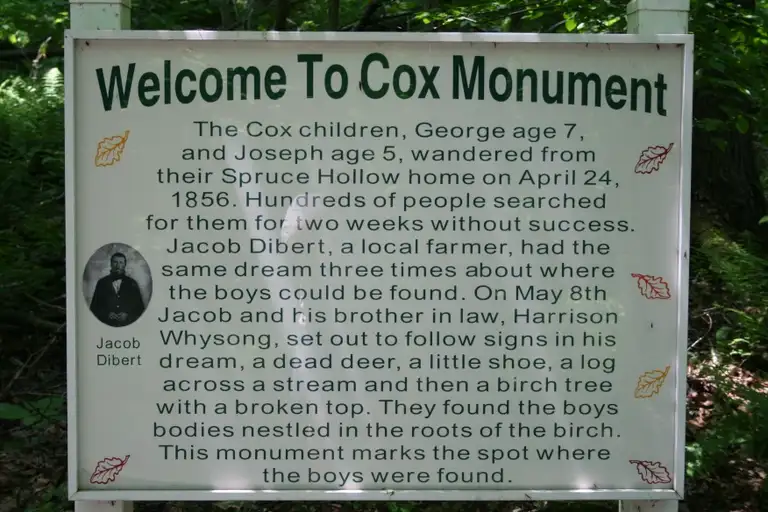

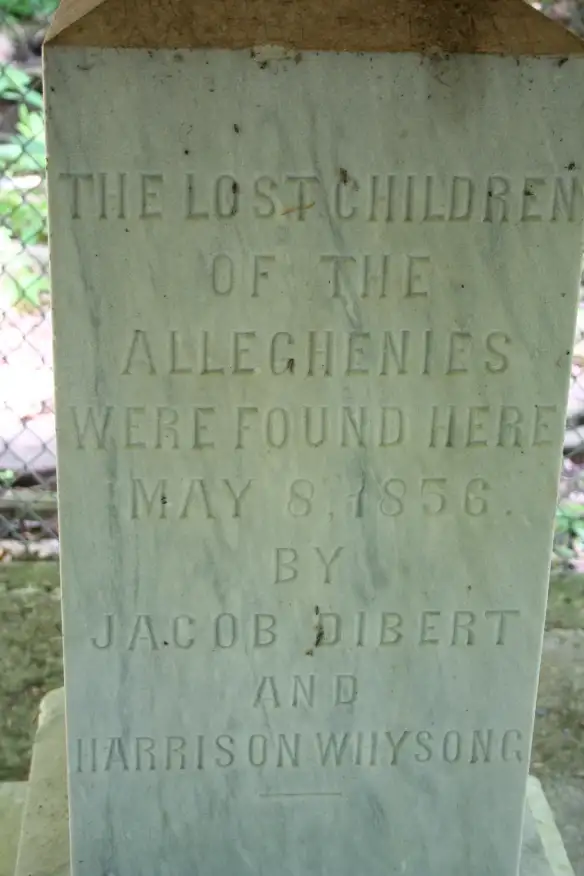

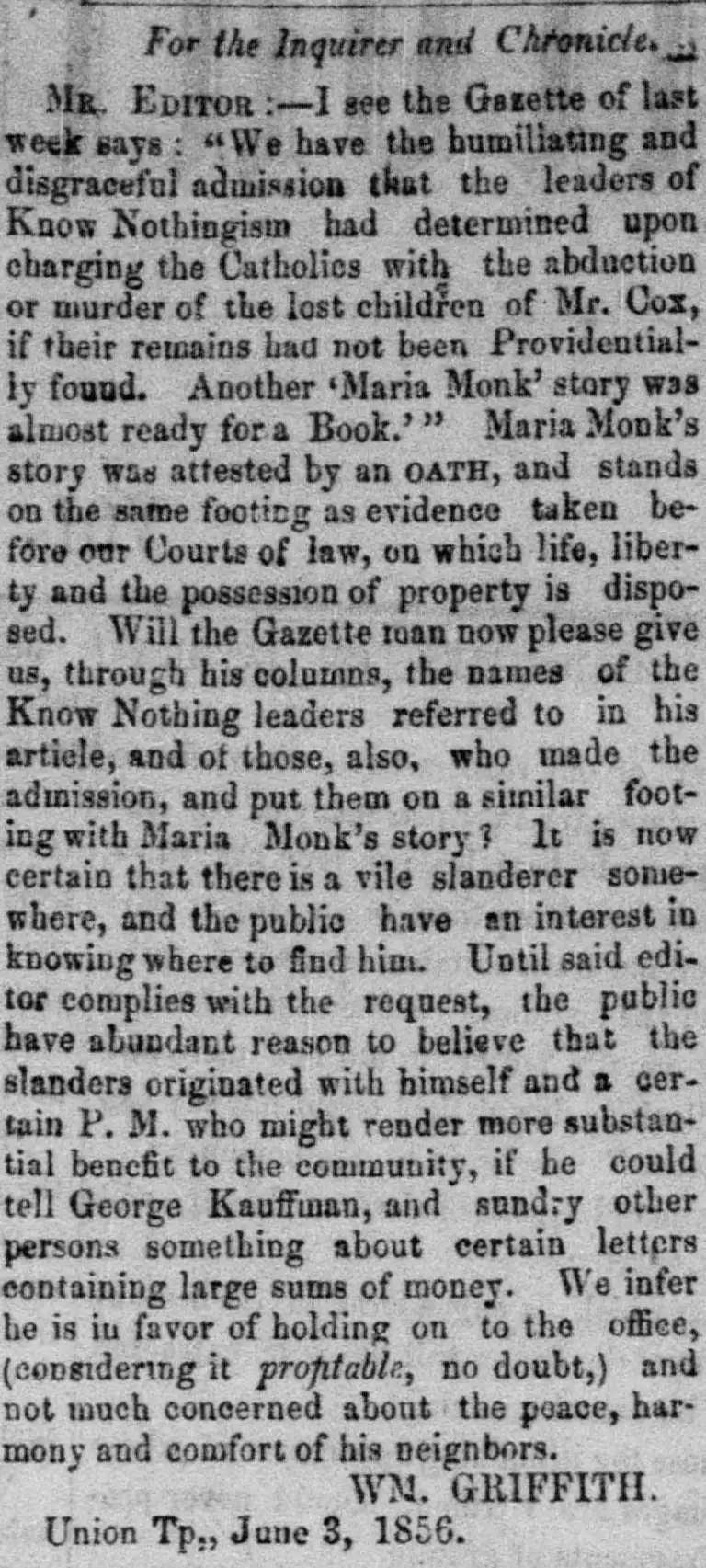

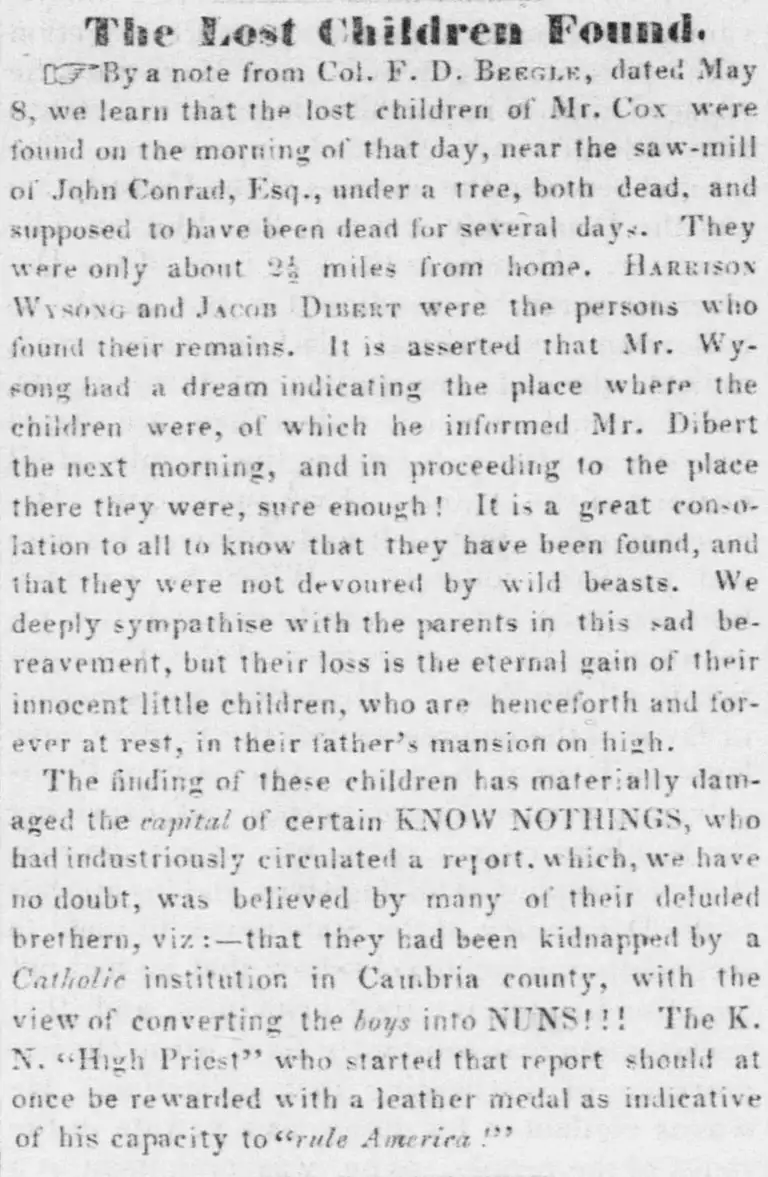

These are photos of where the children were found, the grave site, and a couple of news articles I found at the Library of Congress online digital library.